By Thomas Hauser

On May 4, Saul “Canelo” Alvarez successfully defended his WBC, WBA, and Ring Magazine titles against Danny Jacobs in Las Vegas and added Jacobs’ IBF belt to his wardrobe. With that victory, Alvarez continued to build his legacy the way a fighter’s legacy should be built. Not by self-aggrandizing talk but by deeds in the ring, one fight at a time.

Elite fighters have self-belief. Alvarez believes in himself and radiates quiet confidence without the loud bravado often associated with boxing. He chooses his words carefully when speaking in public and keeps his guard up during interviews as he does in the ring.

Alvarez has the mindset of a fighter. He’s goal-oriented and fundamentally sound with speed, power, and a solid chin. Now 28, he began boxing professionally at age 15 and has compiled a 51-1-2 ring ledger. One of the draws came when he was 15 years old. The other was against Gennadiy Golovkin. The loss was to Floyd Mayweather when Mayweather was at his peak and Alvarez had yet to mature as a fighter.

Alvarez didn’t rest on his early success. He has worked hard to get better and tested himself at every level. He’s willing to fight quality opponents who are good enough to beat him. Three of his last four bouts have been against Golovkin (twice) and Jacobs. He embraces challenges.

There was a blip on the radar screen in February 2018 when urine samples that Alvarez provided to the Voluntary Anti-Doping Association tested positive for clenbuterol, a banned substance. The amount of the drug in his system was consistent with the ingestion of tainted beef. But a boxer is responsible for what goes into his body. Alvarez agreed to a six-month suspension and paid $50,000 out of his own pocket for year-round VADA testing. Since then, he has been tested more thoroughly by VADA than any boxer ever, always without complaint and never with an adverse test result.

“There will always be critics,” Alvarez says. “It comes with success. But I love what I do. I truly love boxing. When I started as a young kid, I always dreamed of becoming a world champion. As I learned with experience, I started challenging myself more and saying, ‘Why one championship? I can go on and win more.’ I’m still growing and seeing this process. That’s what motivates me, to continue writing history and to continue reaching those goals. I want to be remembered as one of the greats in boxing. That’s why I continue to work hard and continue taking on these type of fights, so I can continue writing history.”

Daniel Jacobs came into the ring against Alvarez with 35 victories and two defeats. But despite being the IBF 160-pound champion and having held a WBA belt in the past, he’d never been The Man in the middleweight division. Early in his career, he suffered a fifth-round demolition at the hands of Dmitry Pirog. Two years ago, he was on the short end of a close decision against Golovkin.

“I’m more of a threat than a superstar,” Jacobs says. “So sometimes, when they talk about big fights, I get left out of the equation. Controversy sells, but that’s not who I am. That’s not where I came from. I’m not sure if that’s why I’m not a household name, but I can’t concentrate on that. I stay true to who I am and how I was raised. I’ll always keep that integrity and try to be a stand-up guy. Also, by having a son, I know he watches everything that I do, and I can’t be acting up and being goofy to get more ratings.”

Jacobs is a good representative for boxing. He also takes pride in being a symbol of hope for cancer survivors, having overcome a harrowing illness to get to where he is today.

Canelo-Jacobs was streamed live by DAZN, which hopes to become “the Netflix of sports.” The service is currently available in nine countries – Austria, Brazil, Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, Switzerland and the United States – with further expansion planned. There was skepticism when it was announced in May 2018 that DAZN would invest at least a billion dollars in boxing over its first eight years in the United States. That number now appears to be accurate in light of the $365 million contract that the streaming service has entered into with Alvarez and Golden Boy and its recent three-year, six-fight deal with Golovkin .

DAZN’s entry into boxing sparked a bidding war with ESPN and Premier Boxing Champions that has seen purses for a handful of fighters rise to extraordinary levels. One would expect this to result in the best fighting the best. But overall, that hasn’t been the case. Instead, fans have been subjected to a plethora of one-sided fights and boring matchups.

Within that milieu, Canelo-Jacobs was a welcome relief. Unlike the other powers that be in boxing, DAZN wasn’t protecting its franchise fighter. It was putting him in tough. And Alvarez was a willing participant.

The early buildup to Canelo-Jacobs was dominated by talk of whether Jacobs could get a fair shake from the judges in Las Vegas. Alvarez had fought Golovkin twice in Sin City en route to a controversial draw in their first encounter and a split-decision victory in the rematch. Jacobs offered the opinion that “the second fight was closer but I thought Golovkin beat Canelo both times.” Then he added, “It’s a little annoying to have to keep talking about the judges and Canelo getting favoritism. But it’s also a fact in most people’s mind, so that’s why it comes up so much.”

When asked about the Jacobs camp’s repeated references to “Las Vegas scoring,” Alvarez responded, “They’re making excuses already for his defeat.”

Alvarez also voiced the view regarding Golovkin-Jacobs (which was contested in New York) that, “The fight was close; could have been to anyone. For me personally, Jacobs won the fight.”

Ultimately, the same three judges who worked the Canelo-Golovkin rematch – Dave Moretti, Steve Weisfeld, and Glenn Feldman – were chosen for Canelo-Jacobs. Moretti had scored Canelo-Golovkin I for Golovkin and the rematch for Alvarez. Weisfeld scored the rematch for Alvarez, while Feldman had it even.

The Canelo-Jacobs promotion was marked by good will and mutual respect between the camps.

“He’s a complete fighter,” Alvarez said of Jacobs. “He can box, punch. He’s tall, agile. It’s going to be a very difficult fight, especially in the first few rounds until I start adapting and imposing my style. In boxing, anything can happen. That’s why today I train harder than ever, so that it doesn’t happen.”

“It has never been my intention in the lead-up to any fight to create animosity to sell the fight or to bash my opponent,” Jacobs responded in kind. “Never have I ever wanted to do that. It has never been in my nature. So for me, this has been one of the best promotions that I’ve been a part of because I share the same ideas with my opponent, which is being professional and let our skills and what we bring to the table speak for itself. I’m grateful for that; that we don’t have to go out there and be goofy or go out there and be someone who we aren’t. That’s a breath of fresh air for me.”

But when fight week arrived, the promotion was struggling a bit.

Canelo-Jacobs was part of a nine-day feast on DAZN that saw a super-flyweight championship rematch between Srisaket Sor Rungvisai and Juan Francisco Estrada, two World Boxing Super Series semifinal bouts, and Alvarez (the most bankable fighter in the world) against a dangerous challenger. As DAZN executive vice president for North America Joseph Markowski noted, “The only thing missing is the pay-per-view price tag.”

However, the days when Las Vegas stopped for a big fight are pretty much gone. The MGM Grand was the host hotel for Canelo-Jacobs, but the Billboard Music Awards were a higher priority. The fight-week media center, traditionally in Studios A and B, was relocated to the Premier Ballroom on the third floor of the adjacent MGM Grand Conference Center, a 20-minute walk from the heart of the hotel.

Another problem the promotion faced was that, while DAZN has some excellent public relations personnel, the subscription service isn’t wired into the minds of boxing fans the way HBO was and Showtime is, nor does it have the benefit of a promotional platform like ESPN or Fox.

Alvarez had fought four times at the T-Mobile Arena – against Golovkin (twice) Julio Cesar Chavez Jr., and Amir Khan – generating almost $70 million in ticket sales. Overall, he’d headlined nine fight cards in Las Vegas, grossing more than $115 million in ticket revenue. But despite Canelo-Jacobs being on Cinco de Mayo weekend, ticket sales were falling short of expectations. Ultimately, an announced crowd of 20,203 (just short of capacity) was on hand for the proceedings. However, some tickets were available online for less than face value.

The nights get longer for most fighters during the week of a fight. More than anyone else, they understand and feel the risks involved and the weight upon their shoulders. They sleep more fitfully as the big night approaches.

Alvarez seemed immune to that. Throughout fight week, he projected as being comfortable with who and where he was. The only irritation he showed was a residue of resentment toward Golovkin and trainer Abel Sanchez as a consequence of comments they’d made last year regarding performance enhancing drugs and, in the case of Sanchez, Alvarez’s Mexican heritage. But when asked about Golovkin’s recent dismissal of Sanchez as his trainer, Alvarez answered simply, “I have no comment on that. To each his own.”

Jacobs, perhaps in an effort to lobby the judges, took advantage of several media sitdowns to voice the theme, “Canelo fights for 30 seconds a round. I’ll be much more active than that on Saturday night. Canelo likes to fight in spurts. I’ll be fighting for three minutes of every round.”

Taking stock of where he was in his ring career, Jacobs further proclaimed, “I’m having a great time. This is what you dream of when you put the gloves on for the first time. Right now, Canelo is the face of boxing. I want that to be me.”

Then, at the weigh-in on Friday, the cordial relations came to an end.

Jacobs tipped the scale at the middleweight limit of 160 pounds, Alvarez at 159.6. The fighters were brought together for the ritual staredown – boxing’s most idiotic ritual. And Jacobs stepped out of character, pushing his head forward into Alvarez’s space. Maybe he was trying to intimidate Alvarez. Maybe he was trying to send a message to the judges: “I’m a warrior; I’m coming to fight.” Alvarez shoved him. They exchanged uncomplimentary words having to do with sexual intercourse and their respective mothers (with Jacobs again taking the lead). And the era of good feeling was over.

By the day of the fight, the odds (which had opened at 3-to-1) were approaching 4-to-1 in Alvarez’s favor.

“Jacobs can pose problems for anyone,” Alvarez acknowledged. “He’s a strong fighter, a big fighter. That’s why I prepare for the fight.”

When it was pointed out that Jacobs was known for being strong-willed, Alvarez responded, “He’s strong-minded. I’m strong-minded too. That’s only part of boxing.”

Alvarez had the support of an entire country. Jacobs had the support of a relatively small boxing community in New York. But the fans can’t fight, and the outcome of the bout was by no means a foregone conclusion.

Mentally and physically, Jacobs is a better fighter now than he was in 2010 when he was knocked out by Pirog. And in some ways, the Golovkin fight (which Jacobs also lost) was a plus for him. He fought Golovkin as competitively as Alvarez had.

Alvarez has had trouble with slick boxers like Floyd Mayweather, Erislandy Lara, and Austin Trout. Even Amir Khan posed problems until he tired after four rounds. Jacobs was planning to outbox Alvarez; the fewer firefights, the better. Alvarez, he hoped, would have trouble finding him. And when he did find him, Jacobs can punch.

“Canelo isn’t going to dictate the pace of the fight. I will,” Jacobs posited. “For me, it’s about establishing my style early. I’m a versatile fighter. I can do a lot of different things in the ring. Box, punch, go forward, go back. I go southpaw from time to time. As a fighter, you have to build. You have to get experience. This isn’t my first rodeo. In terms of my physical abilities and what I know, I’m a better fighter now than I ever was. I’m in my prime. I’m super-confident. This is my chance at greatness.”

And there was another factor that weighed in Jacob’s favor – size. At 6-feet tall, he had a four-inch height advantage over Alvarez, a comparable advantage in reach, and was expected to enter the ring with a 10-pound cushion in weight.

The contract for Canelo-Jacobs included a rehydration clause that required each fighter to weigh in a second time at 8 a.m. on the morning of the fight with neither fighter allowed to exceed 170 pounds (10 pounds over the official middleweight limit). The penalty for missing weight was $250,000 per pound or any portion thereof.

Alvarez weighed 169 pounds at the same-day weigh-in. Jacobs registered 173.6. That seemed like more than an innocent mistake.

The “official” purses for Canelo-Jacobs were $35 million for Canelo and $2.5 million for Jacobs. But ESPN.com reported that Jacobs was guaranteed a minimum of $10 million for the fight. Coming in 3.6 pounds over the contractual weight limit – and with the likelihood that he’d gain at least five pounds more before the opening bell – gave Jacobs a significant advantage. If he’d won on Saturday night, it would have been a good investment. But he lost, which left him lighter in the wallet and with a bit of tarnish on his reputation.

Wearing a white track suit with gold trim, Canelo Alvarez arrived at T-Mobile Arena on Saturday night at 6 p.m. The partition between dressing rooms No. 7 and No. 8 had been removed, leaving ample space for the substantial entourage that accompanied him. Black sofas, folding black-cushioned chairs, and four long tables covered with black cloth ringed the room.

Chepo and Eddy Reynoso (Alvarez’s manager and trainer respectively) unpacked their bags, laying out the tools of their trade on two of the tables. Alvarez sat on a sofa at one end of the room beneath a large Mexican flag, took out a smart phone, and began texting. From time to time, he looked at a large TV monitor mounted on the wall that was displaying the DAZN telecast.

There were 70 people in the room. Crews from several Mexican television networks conducted interviews. Alvarez’s personal camera crew and a team from DAZN were also there. Ten more photographers took still photos. Chepo watched it all with the look of a man who wished the interviews would end so the team could get down to business.

IBF supervisor Randy Neumann came in to get Alvarez’s signature on the sanctioning body’s bout agreement. Neumann was wearing a tie emblazoned with images of John L. Sullivan.

“Who is that?” Canelo queried.

“John L. Sullivan,” Neumann answered. “He was a great champion.”

“Oh. I think it is Pancho Villa.”

Alvarez’s longtime girlfriend brought their daughter, Maria Fernanda Alvarez, into the room. This was Maria’s third pre-fight dressing room experience with her father. Her first appearance had been at Canelo-Golovkin II when she wasn’t old enough to walk. Now she was able navigate on her own and made her way to her father.

Canelo was handed a pink balloon and blew it up. Maria backed away in fear. Canelo let the air out slowly and she returned. The process was repeated several times. Finally, Canelo knotted the end of the balloon and handed it to Maria, who embraced it.

Golden Boy matchmaker Roberto Diaz, who monitors Alvarez’s dressing room on fight nights, addressed the multitude.

“Guys, can we wrap it up with the cameras now.”

There was partial compliance.

“Cameras, please,” Diaz urged.

Maria and her mother left. Thirty people remained, most of them wearing Team Alvarez track suits.

At 6:45, Alvarez took off his shoes, socks and track suit and pulled a latex sheath over his left knee. Then he put on the socks, shoes and trunks he would wear into the ring and tied a red weave bracelet over his left sock just above the shoetop. Ramiro Gonzalez, a Golden Boy publicist and longtime friend, had brought the bracelet to a priest to be blessed, a ritual that he and Alvarez follow before each fight.

Mike Bazzel, one of Jacobs’ cornermen, came in to watch Alvarez’s hands being wrapped. Eddy Reynoso worked quickly, right hand first. While the wrapping was underway, Nevada State Athletic Commission executive director Bob Bennett entered with assorted dignitaries, sanctioning body officials and referee Tony Weeks.

Weeks gave Alvarez his pre-fight instructions with NSAC chief inspector Francisco Soto translating into Spanish. Then it was Soto’s turn to address the room.

“Ladies and gentleman,” he said authoritatively. “I now need all of you to exit.”

Alvarez hugged a dozen entourage members as they left.

“Okay,” Soto said to those who had stayed behind. “I need everybody to start moving. Please!”

Foremost among the departing were Usher and Maluma.

Eddy applied Vaseline to Alvarez’s face and arms.

A DAZN technician wired Eddy and Chepo for sound.

Andre Rozier, Jacobs’ trainer, came in to watch Alvarez being gloved up.

The final preliminary fight – Vergil Ortiz Jr. vs. Mauricio Herrera – came on the TV monitor.

Alvarez’s emotions rarely vary in the dressing room before a fight. He’s always calm and low-key. Now he shadow-boxed a bit and paced back and forth, looking at the monitor from time to time.

DAZN production coordinator Tami Cotel came in and announced, “After this fight ends, it will be 20 minutes before you walk.”

Ortiz bludgeoned Herrera into submission in the third round.

Alvarez sat on a sofa, alone with his thoughts.

“How do you feel?” Gonzalez asked.

“I’m happy,” Alvarez answered.

Gennady Golovkin appeared on the TV monitor.

“He looks old,” Gonzalez noted.

“He is old,” Alvarez said.

At 8:15, Alvarez began hitting the pads with Eddy Reynoso, the first in a series of exercises designed to ready him for combat.

Cotel reappeared.

“The anthems are next,” she announced.

Alvarez stood at attention, watching the TV screen as the Mexican and American anthems sounded.

Chepo draped a white-and-gold serape over his shoulders.

In a matter of minutes, Alvarez would climb into a small enclosure that was both a stage and a cage. Twenty thousand people in the arena would be focused on his every move. Millions more would be watching on electronic platforms around the world. Most would be rooting for him to succeed. Some would hope that he was beaten into unconsciousness. Only a handful would see or feel the humanity in him. He’d be a symbol, a commodity, an action video game figure come to life. That’s all.

If Alvarez were to be knocked flat on his back, he’d find himself staring up at the cupola of the video board suspended above the ring. The inside of the cupola is black, as dark as a nighttime sky when the moon and stars are in hiding. The referee would flash fingers in his face. Optimally, he’d recognize the numbers from the start of the count. If the first number he heard was “seven,” he’d be in trouble. As he rose, the black above would give way to a swirling image of the crowd. The roar would be deafening.

He wouldn’t think about whether or not he was fit to continue. It wasn’t his job to assess that. Maybe he’d be hurt. Hurt as in physical pain. Or worse, hurt as in being unable to fully control the movement of his body. If the referee asked, “Are you all right? Do you want to continue?” he’d answer “yes” even though some part of his mind and body – his instinct for self-preservation – might be shouting “No!”

If the fight continued, the same man who’d knocked him down would try to destroy him. The roar of the crowd wouldn’t stop. Alvarez would be in the fire. And when it was over, the people who’d been watching would go on with their lives. They might talk about the fight, but they wouldn’t have bumps and bruises and swelling and pain. If their thoughts were fuzzy, it would be from too many beers, not punches they’d taken.

Alvarez had never been knocked down in his ring career. But he knew what he’d done to Amir Khan, James Kirkland, and so many other fighters. Could it happen to him? Of course, it could.

At a sitdown with a small group of reporters just before the final pre-fight press conference, Jacobs had said, “I want this to be one of those fights that people talk about for years to come.” For weeks, he’d repeated the mantra, “Canelo only fights for 30 seconds a round. I’ll be active for all three minutes.” Jacobs had talked the talk and gotten in Alvarez’s face at the weigh-in. He’d waxed eloquent about being the bigger stronger fighter.

But when the moment of reckoning came, Jacobs fought a safety-first fight. Alvarez might not have wanted the victory more, but he fought like he did.

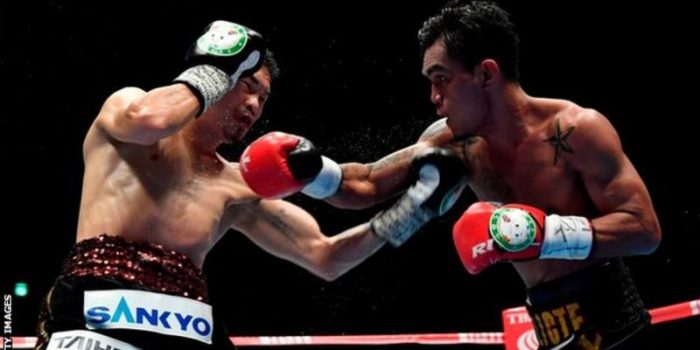

Round 1 was a feeling out stanza. Alvarez moved forward, looking to engage while Jacobs moved away, right hand held defensively by his chin rather than cocked to fire. As the bout progressed, Alvarez began closing the distance between them. Jacobs transitioned to southpaw from time to time, but it wasn’t a particularly effective maneuver. Alvarez’s head movement kept Jacobs from establishing his jab, and Jacobs didn’t do anything to take Alvarez out of his rhythm.

It’s easy to say that a fighter should fight more aggressively. But that only works if he can hit his opponent and not get hit harder in return. Alvarez is hard to hit and one of the best counterpunchers in boxing. The rounds were close, but Canelo was winning most of them. After eight rounds, he led by four points on each judge’s scorecard.

Two minutes into round nine, Jacobs landed his best punch of the fight – a straight left up top from a southpaw stance. Alvarez took it well. Thereafter, Jacobs held his ground more and fought more aggressively. But it was too little too late. The 116-112, 115-113, 115-113 decision in Alvarez’s favor was on the mark.

The big “if” from Jacobs’ perspective was what would have happened had he fought more aggressively from the start. But he didn’t, and that was that. He gave away the early rounds, and Canelo wouldn’t give them back.

After the bout, there was the usual bedlam in Alvarez’s post-fight dressing room. Family and friends exchanged hugs and kisses amidst laughter and cheers.

Chepo and Eddy Reynoso stood quietly to the side, each with a satisfied look on his face. The odds are overwhelmingly against a young man journeying from poverty to international acclaim with his fists. But by definition, a chosen few will succeed where others fail. Years ago, the Reynosos took charge of a boy. No matter how much natural ability Alvarez has been blessed with, someone had to teach him to box.

Meanwhile, Maria Fernanda Alvarez was toddling around the room when she spied four championship belts spread out on a sofa. Colorful, shiny, better than a balloon. The WBC championship belt captured her attention first. But the WBA belt had more gold, and the Ring belt was the most colorful. So she moved joyfully from one to the next.

Canelo – his face a bit swollen beneath his right eye but otherwise unmarked – joined her.

Maria pressed her hand against one of the belts and uttered what sounded like one of the first words a child learns regardless of language.

“Mia (mine).”

“No,” Canelo said with a smile. “Es de Papa.”

Article courtesy of Thomas Hauser & Sporting News

Photo courtesy of Ed Mulholland/Matchroom Boxing

Recent Comments