By Melanie Lloyd

“If there was something wrong before the fight, that’s an excuse, and Josh won’t give excuses.” Sean Murphy

Anthony Joshua’s career was forged by Sean Murphy, who tells Sky Sports about tough beginnings in boxing, AJ’s raw talent, and fighting back from defeat.

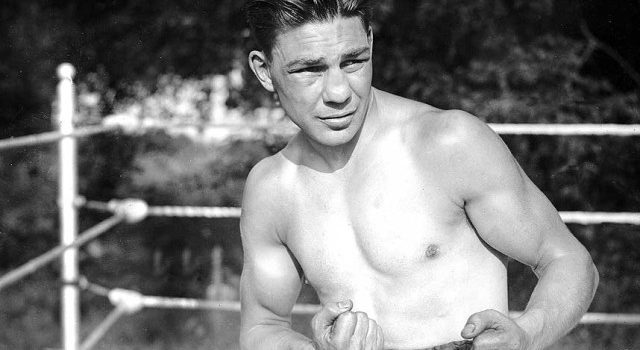

Over the past decade, Sean Murphy has become widely known as “Anthony Joshua’s first amateur coach.” But 30 years ago when AJ was a babe in arms, the boxing world knew this straight-talking advocator of old-school values as the man who terrorised the featherweight division with his explosive fighting style. He was twice British champion, and he delivered dynamite every time he stepped through the ropes.

To the Murphy clan, boxing is second nature. When Sean’s father relocated to London from Ireland in the 1960s, he boxed at St Pancras alongside Roy Francis, the well-known star referee. Sean was 11 years old when his father began teaching him the rudiments of boxing at home, but it was actually his mum who put her foot down, as he explained to Sky Sports, “I was always a very boisterous kid. My two sons have got ADHD and dyslexia, and think I probably had it too. But, back then, these things were unheard of. I was always in the bottom groups at school, but I had a lot of common sense. My dad broke his hand twice playing hurling, so he gave up boxing, but he got me interested when he started training me in the house.”

“Because I was so hyperactive, it got to the point where my mum said to my dad, ‘can you take him somewhere and get him involved in something?’ So my dad took me to St Albans boxing club when I was 12. Within six weeks, I’d had my medical and I was boxing. When we started, my dad wasn’t going to get involved, but they asked him to help them out and my dad soon became head coach at the club, he was doing the matchmaking, and he was running things.”

“I never won a national schoolboy championship. But, as a schoolboy, you don’t get the rub of the green sometimes. One year, I’d had two abscesses and my face was really swollen up. I was meant to be boxing in the schoolboys on the Saturday. I went to the dentist, they took my two teeth out, and the abscesses went down. My dad said ‘Just come to the schoolboys. You’ll only have to weigh in. You won’t box.’ So I got there, I weighed in, and I ended up having two fights and I won the Home Counties.”

During the two years he boxed as a senior, Sean had 25 internationals for England and won 21. He won two ABA championships, a Commonwealth gold medal, the Canada Cup and the Acropolis Cup. “I’ve seen so much of the world through being on the England squad, boxing in places like East Germany, West Germany and Canada. Then, in 1986, I made the decision to go pro at the age of 21. I turned over with Frank Warren, and I had Ernie Fossey and Jimmy Tibbs in my corner. Ernie Fossey was Frank Warren’s right-hand man, and I was Ernie Fossey’s blue-eyed boy. I used to pick Ernie up from his house in my car and drive him to the gym. Ernie never used to do pads, so I used to get a lot of pad-work off Jimmy, which was brilliant.

“I was a very aggressive, come-forward sort of fighter. I could box as well. But sometimes, I’d get in the ring and my heart would take over. I might get caught with a shot, and then I’d want to have a tear-up. The hardest fight I ever had was against Mike Whalley in an eliminator for the British title. It was the first time I ever went 10 rounds. I hit him with everything and he was still there at the end, and he didn’t have a mark on him. I forgot my boxing boots and I borrowed a pair that were too big for me, so I had a blister on my foot. My hands were so swollen up that I couldn’t even do my shirt up afterwards, and my face was like the ‘Elephant Man’. Even though I got the decision, if you looked at me and you looked at Mike Whalley, you’d have thought he won the fight.”

The fight that Sean is often fondly remembered for is his dramatic third round stoppage of John Doherty at the City Hall in St Albans for the vacant British Featherweight title in May 1990. Early in the second round, Sean sustained a horrific cut across the bridge of his nose. He had sold £5,000 worth of tickets that night and there were anxious moments as the referee stopped the action to examine the damage. Ernie Fossey worked his magic in the corner, and Sean came out for the third and stopped the Yorkshireman, having put him down twice. It was a dream come true for Sean to win the British title in front of his home fans, and he wasted no time in jumping on to the ropes to salute the crowd. “I had a good following. I used to sell hundreds of tickets because we’re Irish and I’ve got a big family. My dad used to do two or three coachloads every fight. But the funny thing about the crowd that night was I had an out of body experience. I was looking out of the ring and I could see everybody in the crowd in precise detail. It was like everything was going in slow motion. I saw my father-in-law. I saw a girl that used to work in the local pub. It was mad, and I can never explain it.”

Sean’s final fight was in February 1994. “Ernie rings me up and he says ‘I’ve got you a British & Commonwealth title fight at lightweight against Billy Schwer.’ Billy’s record was 21-1 and he was two weights above me, so it wasn’t an easy fight. But I got eight grand for the fight, so I decided to take it for the money. After I got off the phone to Ernie, I said to my wife ‘Whatever happens, if I win or lose, I’m going to retire.’ I’d lost the desire for the training. It was becoming a chore. So I should really have never got in the ring with Billy Schwer. Believe it or not, it weren’t until about three weeks ago that I actually watched that fight for the first time. I’ve gone straight out there and had a war. I got put down three times in one round, and I was thinking ‘I’m proud of myself because I keep getting up.’ He was putting me down, but he couldn’t keep me down. I’ve never been put to sleep where I’ve been out for the count of 10.”

“When I walked away from the sport, I had a few clubs ringing me up to ask me if I wanted to go and help them train. But I didn’t do it then because I knew that, if I went back, I’d want to box again. So I had three years away from boxing and then, the same as my dad, I started training my boy, Danny, to box at home. He ended up going to Finchley, and I’d just sit at the back as a parent. After about four weeks, they were short of trainers one night and they asked me to give them a hand, so that’s how it started.

“My wife, Tracey, does the matchmaking. She’ll make the bouts, and I’d never question her because she’s been with me since she was 15. When we were young and all our mates were going out clubbing at the weekends, I’d be training for a fight and she’d sit in with me watching TV. She’s watched my amateur career and my pro career right through.”

“When Josh first came to Finchley with his cousin, Ben Lleyemi, I think he was getting into a bit of strife in the street. Back then, Josh was only weighing 92 kilos, but the power was there right from the start. One night, we were on the pads and, when they’re going to throw a body shot, you put the pad roughly at their waist height. So I’ve gone ‘One, two, left hook to the body’ and, because he’s so tall, I’ve left the pad up a little bit high, he’s missed the pad and he’s hit me in the body with a left hook. I couldn’t breathe, but I’ve took the shot and I’ve stepped back. Then he’s come in for more, so I’ve gone down on one knee. I was all right. He just winded me. But, if I’d been at my boxing weight, he would have cracked my ribs, which just goes to show how Andy Ruiz’s fat provided protection.”

“Josh’s first bout was in November 2008 at the Boston Dome against a boy called Brede. The kid was really only a blown up light-heavyweight, and Josh put him down with a jab and he stopped him in the first round. When you watch the tape, you can see Josh’s dad running up and down at the ringside. I’m actually training his friend’s son now. He’s a super-heavyweight, and Josh’s dad came to see me and he went ‘Can you look after him?’ But they get looked after here anyway. All of the fighters in the club are my boxing family.”

“Josh’s second bout was against Dillian Whyte, and it turned out that he’d had 200-odd kickboxing fights, although I didn’t know that when I accepted the fight. In Josh’s sixth bout, he boxed a boy from Switzerland in the Haringey Box Cup. In his eighth bout, he boxed Frazer Clarke, who was a GB boy, and he beat Frazer Clarke, so he was getting international experience from a very early stage in his amateur career. But you can bring a boy so far as an amateur, and then you’ve got to know when to do the right thing to let them get to where they want to be. Just before the London Olympics, Josh walked in the gym and he gave me a glove. I said ‘What’s this?’ He said ‘It’s been signed by all the Olympic boxing team. I got it for you.’ I had a lump in my throat, and I don’t really show much emotion. When you look at what he achieved in his short amateur career, it’s phenomenal.”

When AJ made his professional debut 10 days before his 24th birthday, the boxing world waited with baited breath. He was such an electric prospect, and yet he possessed a disarming form of innocence. When he visited Wladimir Klitschko’s training camp in Austria in 2014, it was easy to fall in love with the statuesque man-child giving that wide-eyed interview from the ring apron. His earnest desire to absorb every bit of knowledge that he could from the experience of being there, coupled with his sincere respect for his host, warmed our hearts. At the same time, there was an underlying energy about him that gave us a glimpse of a man that you wouldn’t want to mess about with and, let’s face it, there is nothing more intoxicating to us boxing fans than a lovable rogue.

Fast-forward three years to that sensational night when the protégé marched out to face the master to the roar of the 90,000 crowd at Wembley Stadium, and nobody can say that AJ didn’t do us proud. However, as he marched up the gangplank to take his place in the centre of all those pyrotechnics, resplendent in white and flashing that smile in every direction, if one looked closely enough, there were still detectable traces of the boy we saw back in Austria.

Sean explained, “I find, even now, he’s a little bit naive. I know he’s very streetwise and all this, but there’s a little kid inside him. I was worried when I saw him walking to the ring for the Klitschko fight, because he didn’t look relaxed. I believed he was going to win, but I thought he looked nervous. When Josh got put down, he was in trouble, but he had the mind-set to take a few rounds off until he felt right and ready to go again. If he hadn’t have done that, if he’d have got up and gone straight out to try and stop Klitschko, he wouldn’t have been world champion. Mind you, I also thought that was the best fight that Klitschko ever had. For someone of his age, I think he’s amazing.”

I remember watching Ruiz in his first season as a pro and thinking ‘He’s a good fighter, this fella.’ I knew he was going to be a harder fight than Jarrell Miller

Sean Murphy

Prior to AJ’s defeat by Andy Ruiz Jr last month, Sean had concerns when the Mexican stepped in as the replacement opponent. “Everyone was thinking Josh was going to blow this man away. The man has never been stopped. He’s had 110 amateur bouts and he’s won 105. That tells you he’s a good fighter. I remember watching Ruiz in his first season as a pro and thinking ‘He’s a good fighter, this fella.’ I knew he was going to be a harder fight than Jarrell Miller. The way Josh was behaving before the fight, something was obviously wrong. But, because of the sort of person Josh is, no one is ever going to find out what actually happened, not until he retires. If there was something wrong before the fight, that’s an excuse, and Josh won’t give excuses.”

“Ruiz’s performance was good. It was tight. I’ve watched the third round over and over again. When Josh put Ruiz down, he put a lovely combination together. But Ruiz weren’t ready to go. Ruiz still knew where he was, and Josh tried to go in and finish him. If he had done that with Klitschko, he would have lost. He did it with Ruiz, and that was his downfall. Josh definitely lost his senses when he got hit at the back of the head, and he should have taken his time and picked his shots a bit more. But the thing is Ruiz has got to the top of the mountain, and you don’t want to try and take something away from him by saying that this happened or that happened. So I think that we should just let Ruiz have his moment.”

Recent Comments