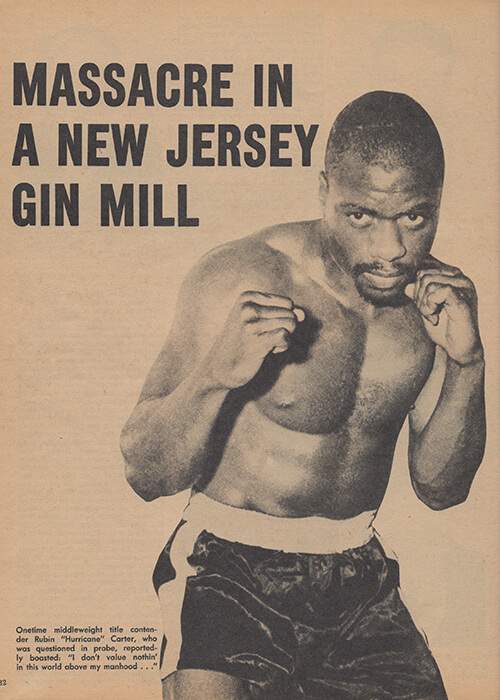

The BBC’s World Service has been investigating three murders that took place at the Lafayette Bar and Grill in Paterson, New Jersey in 1966. Over the past 15 weeks ‘The Hurricane Tapes’ podcast has been broadcast.

Before that, there was simply the Hurricane – Rubin Carter. This is his story.

Warning: This article contains swearing and graphic descriptions of violence.

June, 1966.

It’s muggy in Paterson, despite it being the early hours of the morning.

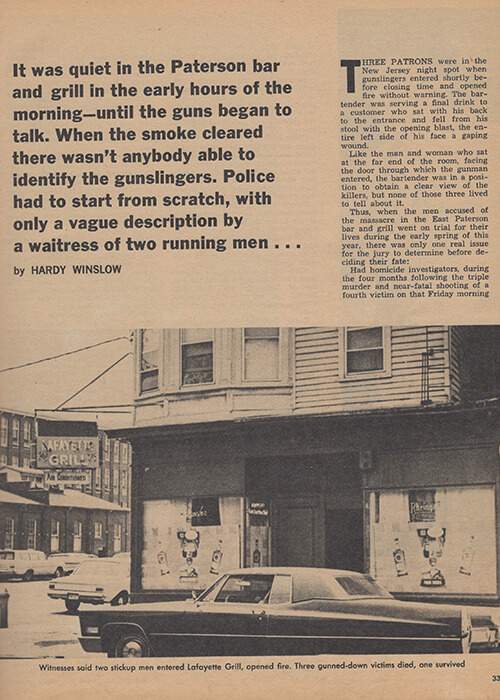

In the Lafayette Bar and Grill, a run-down place on the corner of a run-down area, bartender Jim Oliver is still working.

Fred Nauyoks is sitting opposite him, drink in one hand, cigarette in the other, talking to Willie Marins.

At the edge of the bar sits Hazel Tanis, who has called in for a drink after finishing her waitressing shift.

The Lafayette Bar and Grill interior in June 1966

Two black men enter the bar. It’s unusual; the Lafayette doesn’t serve black patrons.

Even more unusual is what they hold in their hands. One has a shotgun, the other a pistol.

Oliver throws a bottle at the assailants and turns his back on them.

In a heartbeat, he is on the floor, his spinal cord severed by a shotgun blast.

Nauyoks doesn’t have a chance to move from his stool. He dies in his seat, cigarette still burning in his hand, a bullet in the back of his head.

Fred Nauyoks (2) is the next to be shot, taking a bullet to the back of the head

Marins turns his head at both the right and wrong moment. A bullet passes through his eye and explodes out of his forehand. He passes out.

Willie Marins (3) is also shot in the head, but does not die from the injury

Tanis jumps off her seat and is trying to hide when the gunmen find her.

They empty their remaining bullets into her body, leaving her bleeding on the bar-room floor, before turning and disappearing into the New Jersey night.

Hazel Tanis (4) has time to leave her seat, but not enough to flee, becoming the fourth to be shot

Eight bullets. Two dead. One dying. One seriously injured. All in 20 seconds.

Rubin Carter always remembered a childhood hunting trip.

His father tracked squirrels and raccoons to feed the family in a United States crippled by the Great Depression of the 1930s. He took young Rubin and his uncles with him on one trip.

As they drove through the New Jersey woodland, they noticed they were being followed by a truck. The driver, a white man, tried to run them off the road.

Carter thought the driver was acting like it was his right to target them.

Carter’s father stopped. So did the trucker. Carter’s father got out. So did the trucker. Carter’s uncle followed, a shotgun cradled to his chest. The trucker, wisely, fled.

For young Rubin, this act of self-protection, of looking after yourself whoever the opponent, had a lasting effect.

He was a natural leader as a youth, overseeing a gang that would fight other kids in the neighbourhood.

Rubin didn’t kill people,” his cousin Johnny said. “He beat the shit out of them. “He liked to fight, but he wasn’t a violent person.”

His desire to fight didn’t just extend to his own age group.

He was once seen by a preacher stealing clothes. The preacher told Carter’s father. Carter promptly attacked the preacher – a man who was far older than him.

He did enough damage to merit a beating from his father, who cracked him in the eye with a belt before calling the police.

“Rubin would grin and slobber when he fought as a kid,” Johnny said. “It wasn’t so much he was a bad or evil guy. He was just who he was.”

What Rubin was, by age 14, was a prisoner.

He stabbed a man he claimed was a paedophile and was sent to Jamesburg, which he referred to as a place “where eight-year-old kids become the prey of 15-year-old killers and rapists”.

His father refused to visit, so Carter put his energy into ruling the roost.

He became one of the toughest in the prison, a person who “if they wanted to beat somebody up, they beat them up, because that’s how they rule”.

Eventually, enough was enough. He broke a window and escaped. For two days he ran, putting 80km between him and the prison.

Patty Valentine is asleep on her couch, the TV still playing in her flat above the Lafayette. Her son is asleep down the hall.

A banging noise wakes her; she assumes it’s Jim, closing up for the night.

She goes to the window on the corner of East 18th and Lafayette and realises the bar is still open, the neon light still shining into her living room.

Extract from police interview with Patty Valentine

Valentine hears a voice – a frightened, unidentifiable voice, that cries out “oh no”.

She goes to her front window before moving into her bedroom, which overlooks Lafayette Street. A white car is parked in the middle of the road. Valentine sees it has New York licence plates – dark blue with yellow and gold lettering – and tail lights shaped like triangles.

She stands and watches two black men leave the bar. One climbs into the driver’s seat, the other the passenger side, and they drive off into the night.

She’s seen enough. Pulling on a raincoat, Valentine heads downstairs and through a side door.

A man tells her to stay away. Glancing inside, Valentine sees Marins holding on to a pole, blood on his forehead.

Instinctively, she walks towards him. As she rounds the pool table, something catches her attention. It’s Tanis. She knows her. She recognises the country club uniform she’s wearing. A black uniform, slowly turning red.

Valentine’s eyes linger on the blood. She takes a second to process it before screaming and running out of the bar and up to her flat.

At 2.34am, the police are called.

After escaping from jail, Carter’s next stop was the army.

He joined in 1954 and was dispatched to Germany, where he took a liking to the bars.

Unsteady on his feet one night, he stumbled across the army boxers midway through a gym session. He turned to their trainer and announced he could beat any man there.

The trainer, spotting the tell-tale sway of alcohol, suggested he return the next day. He did – and proved true to his word.

His transformation from ill-disciplined street fighter to professional boxer had begun.

“Some guys would knock you cold,” his friend Ron Lipton said. “Rubin would paralyse you with a punch.”

Another former sparring partner said his battles with Carter made him quickly realise “boxing wasn’t something I wanted to do with any regularity”.

Carter spent two years honing his skills before being discharged.

Two stints in prison quickly followed – first for skipping jail, then for three apparently spur-of-the-moment muggings.

Carter turned professional boxer the day after being released from prison in September 1961.

A year later, at the iconic Madison Square Garden, he needed just 69 seconds and one punch to knock out Florentino Fernandez. ‘The Hurricane’ was born.

“He was animalistic in the ring because of the fury he would bring on you,” ex-sparring partner Fred Hogan said.

His movements were overwhelming. He brought on the fury. He brought on the ‘Hurricane’.”

Carter grew to hate the name – “I came to realise that this is not me. It was actually a monster” – but the mean, brutal image created a buzz around his fights.

In 1963, the ‘Hurricane’ was set to fight two-division champion Emile Griffith.

Griffith was bisexual. He had been goaded about his sexuality by Benny Paret in the build-up to a previous fight. On fight night, Griffith punched Paret’s head so many times he was carried straight from the ring to hospital and died 10 days later.

Carter wanted Griffith to lose control when they met. In front of the television cameras, he delivered a stinging blow.

“You talk like a champ, but you fight like a woman who deep down wants to be raped.”

The press were in a frenzy. Griffith was furious. He went hard at Carter the next day. Too hard. Carter took aim and floored him in two minutes 13 seconds.

The first paramedic to arrive at the Lafayette Bar slips on the blood that is spreading across the floor.

Two people are dead; Tanis is clinging to life. She and Marins are taken to hospital as detectives, officers and civilians surround the bar.

Less than a mile away, John Artis – a black, 19-year-old track star – is ready for home after an evening’s dancing at the Nite Spot.

Looking around for a lift, Artis sees Carter, a regular he met a couple of weeks before. Artis yells out; Carter throws him the keys to his car – white, with New York plates and triangular tail lights – and tells him to drive.

John Bucks Royster, a drifter who has had too much to drink, gets in the front while Carter lies down across the back seats.

Artis sets off, but six minutes later the interior of the car is lit up by headlights. A police car’s headlights. He pulls over, nervous – he’s never been in any trouble before.

Carter sits up as the police officer leans in and tells them he is “looking for two negroes”. “And any two will do?” Carter replies.

The officer recognises Carter and greets him, then asks to see Artis’ licence. He hands it over and, after it is inspected, Artis is told he can go.

Carter lies back down and directs Artis to his house, wanting to pick up some more money before heading back out to the bars.

Artis pulls up outside Carter’s house. The boxer takes 15 minutes to get in, get some money and get back in the car.

They drop off Bucks Royster, and Artis sets off home, intending to drop off Carter on the way.

He never makes it.

In 1965, Carter – now a husband and father – was set to face Joey Giardello.

Giardello was the world middleweight champion, but Carter was at the peak of his career.

The fight – reigning champion against loose cannon – took place against a backdrop of racial tension.

Carter v Giardello

That same year, there was trouble in Paterson, where Carter lived. What started as a group of black teenagers throwing rocks at cars turned into a three-day race riot, with 200 of the area’s 310 officers on the streets.

Carter never hid his dislike of the police.

In the build-up to the Giardello fight he talked about his love of guns – “We’d go out in the streets and start fighting, anybody, everybody. We used to shoot at folks” – and bragged that he had once stabbed a man “everywhere but the bottom of his feet”.

He also said African Americans should arm themselves for protection.

“If you act like you afraid of me, you better be afraid of me,” he said, “because I would do to you exactly what you would do to me. I’d just do it quicker.”

The light bounced off Carter’s bald head as he entered the ring, clad in silk. Victory would see him take the world title.

He started well, body blow after body blow pushing Giardello back, but he could not deliver the final strike.

They went the full 15 rounds before the referee raised Giardello’s arm above his head.

It was a loss that would start the decline of Carter’s career.

Recent Comments