By Richard Goldstein

Leon Spinks, who scored one of boxing’s greatest upsets when he defeated Muhammad Ali to capture the heavyweight championship in February 1978, but lost his crown in a rematch seven months later and never again found glory in the ring, died on Friday night in Henderson, Nev. He was 67.

His death, in a hospital, was announced by his wife, Brenda Glur Spinks, in a statement released by the family’s public relations representatives. His family announced in December 2019 that he had been hospitalized for treatment of prostate cancer that had spread to his bladder.

Spinks burst into view when he won the Olympic light-heavyweight gold medal and his brother Michael took gold in the middleweight division at the 1976 Montreal Games.

Leon had fought professionally only seven times, with six victories and a draw, before facing Ali at the Las Vegas Hilton on Feb. 15, 1978, in a bout arranged by Bob Arum, one of boxing’s leading promoters.

Ali held the World Boxing Association and World Boxing Council titles. But at 36, though an overwhelming betting favorite, he was past his prime. He weighed in at 224 pounds to Spinks’s 197.

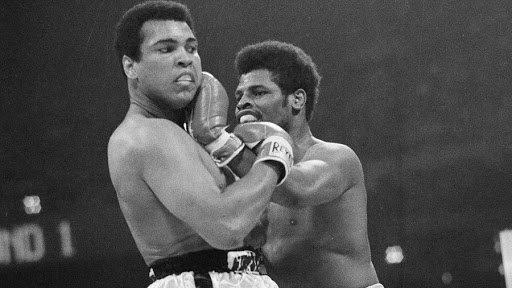

Spinks was a hard-charging brawler, but when he pressured Ali in the ring, the champion resorted to his rope-a-dope strategy, which was aimed at letting an opponent exhaust himself with punches that seldom did damage while Ali rested on the ropes.

The Spinks corner had a strategy of its own, aimed at weakening Ali.

“Jab, jab, jab, that was the plan,” Spinks’s trainer, George Benton, said in the dressing room afterward. “Hit him on the left shoulder all night with that jab.”

Ali rallied in the 15th round, but Spinks warded him off and won a split decision.

At the fight’s end, Ali had purple bruises above and below his right eye. His forehead was swollen near his left eye, and blood dripped from his lower lip.

“He had the will to win and the stamina,” Ali said. “He hit pretty hard.”

A few days after the fight, Spinks appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated, flashing what became a familiar gaptoothed smile.

The World Boxing Council stripped Spinks of its heavyweight title for refusing to make a defense against Ken Norton, its designated challenger, and gave Norton the crown.

Ali had envisioned a rematch with Spinks and promised to “keep movin’, don’t go to the ropes, be in better shape.” The strategy worked.

In September 1978, Ali regained his W.B.A. title, defeating Spinks in a unanimous decision at the Louisiana Superdome before a crowd of some 63,000. This time he tied Spinks up when he charged at him, and he danced and jabbed like the Ali of old.

By 1981, Larry Holmes held the World Boxing Council heavyweight crown. Spinks challenged him that June, losing on a third-round technical knockout. He faced Dwight Muhammad Qawi, the W.B.A. cruiserweight champion, in 1986, losing on a ninth-round technical knockout.

His career by then was mostly in decline, and he had gained a reputation for partying in the midst of his training.

Before the Holmes fight, Sam Solomon, who was Spinks’s trainer early in his pro career, recalled the weeks in the Catskills when Spinks was getting ready for his first Ali fight.

“He’d go to bed at night and turn on his music box real loud and lock his door,” Solomon told The New York Times. “The only way I could find him was to trace his tracks in the snow.” That time, as Ali would soon learn the escapade didn’t harm his chances.

Spinks’s last fight came in December 1995, when he lost a unanimous decision to Fred Houpe in an eight-round bout. Spinks was 42; Houpe was 45 and had not fought since November 1978.

Spinks retired with 26 victories (14 by knockouts), 17 losses and three draws.

Leon Spinks Jr. was born on July 11, 1953, in St. Louis, the oldest of seven children of Leon and Kay Spinks, who separated when he was a child. The family was poor and the neighborhood was tough. He would tell of receiving severe beatings from his father.

A frail youngster, suffering from low blood pressure and asthma, Leon became a target of bullies.

At age 13, he began boxing in a St. Louis gym program created to keep youngsters off the streets. He dropped out of high school in his junior year, joined the Marines, took part in their boxing program and thrived as an amateur in bouts leading up to the Montreal Games.

Spinks had a largely unstable life after retiring from the ring. He said he had lost the money he earned, and he traveled around the country, seeking what jobs he could find. At age 52, he made a stop in Columbus, Ind., where he worked as a Y.M.C.A. custodian and unloaded McDonald’s trucks.

Spinks fathered three sons with a girlfriend, Zadie Mae Calvin, who had grown up in his neighborhood.

One son, Cory, became a welterweight champion, and another, Darrell, had 19 pro fights. His son Leon Calvin, who used his mother’s surname, won two pro bouts before he was shot to death at 19 while fleeing in a car from a party in St. Louis that had turned violent. Leon Calvin’s son, Leon Spinks III, fought in 16 pro bouts.

In addition to his wife, his sons Corey and Darrell, his grandson and his brother Michael, Spinks is survived by seven other siblings: Karen (Spinks) Shanklin, Leland Spinks, Evan MacDonald, Eddie Brooks, Charles Spinks, Lionel Spinks and Patricia Spinks.

On the night he dethroned Ali, Spinks said, he drew on the adversity of his childhood in summoning the strength to persevere.

“My dad had gone around and told people I would never be anything,” Sports Illustrated quoted him as saying. “It hurt me. I’ve never forgotten it. I made up my mind that I was going to be somebody in this world. That whatever price I had to pay, I was going to succeed at something.”

Gillian R. Brassil contributed reporting.

Recent Comments