By Kenny Craven,

The summer of 1988 I drove into a part of Laurel, Mississippi that I had never been in before. I was 18 years old at the time and had heard there was a place on the other side of the tracks that taught boxing. I grew up outside of Laurel but had never seen many parts of the city. I assume the reason was due to the unofficial and unspoken segregation that still existed.

Why would a white boy ever go to the other side of the tracks unless he wanted something, right? I remember driving past the rec center several times before mustering the courage to pull into the parking lot. I was not afraid of boxing; I was afraid of being the only white guy in the room for the first time in my life. I didn’t know why I felt this way, but I felt it all the same. I walk through the front door and meet a janitor mopping the front lobby. “Is this where they teach boxing?” I ask. The man looked at me for a few seconds before answering, “Yeah, they in the back,” as he motioned with his head. I walked through the lobby and on to a basketball court. There was a door down to my right and I could hear the sound of pounding and clinking metal.

As I entered the door I was met with this wave of heat that was almost oppressive. The boys that were working the bags stopped and stared at me. The coaches turned to see what it was that caused such an abrupt stop to their work. I had been in the room no more than 10 seconds and I was pouring sweat. “Hi, my name is Kenny Craven and I want to box,” I say as I reached out my hand to the coach closest to me.

I’m sure at first the team was quite skeptical of me and as to why I was there, but as time went by and I kept showing up the boys started talking to me a little bit. I remember one day we were running through the neighborhood and we passed a house with a spotted pitbull lying under the porch. I was near the back of the group of boys running past the house. As soon as I passed the house of the spotted pitbull, it emerged as if directed by God to devour someone. Little did I know, until it passed up all of my fellow black boxers, it intended on devouring me. I sped up until I was at a full sprint and in the front of the group before the dog gave up chase. A few moments later as I tried to catch my breath and my teammates caught up with me one of them said, “Bro, that dog hates white people.”

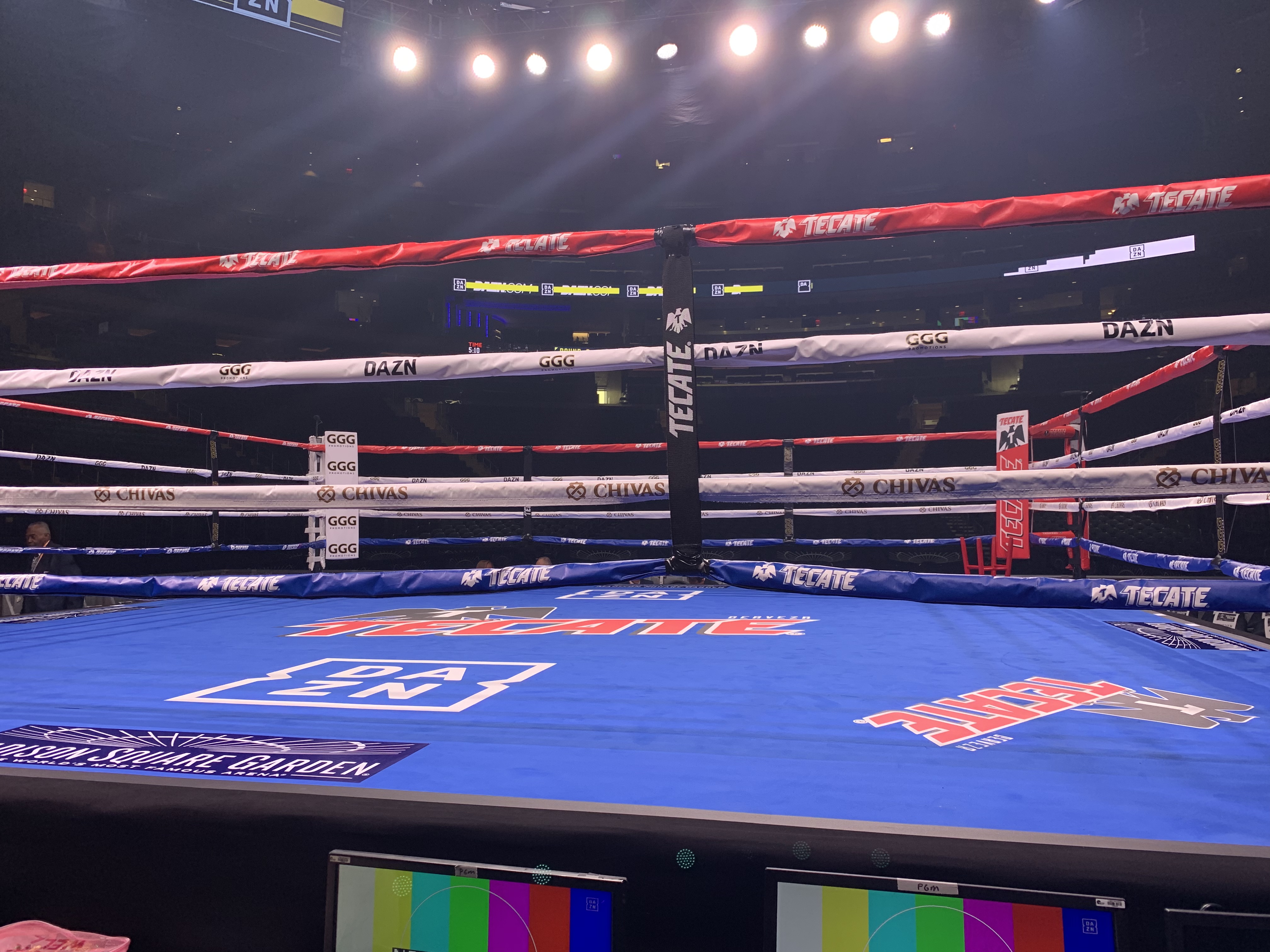

After a few weeks had gone by I remember walking into the gym one day and seeing folding chairs forming a 14 foot square on one end of the basketball court. This, I was about to find out, was our boxing ring. Up until this point all that I had been hitting was a heavy bag. Today would mark my first test, my first sparring experience. I began wrapping my hands while looking through my equipment bag in search of my mouthpiece. I rummaged through my bag at least half a dozen times before conceding that it was not in there. Ok I thought, I’ll just not use one, no big deal.

When it was my turn to spar the coach asked me if I had a mouth piece, of which I said no. He motioned toward a cabinet saying there were a few old ones in it that been used before but I could go wash one off and use it. I found the least dusty one I could see and walked slowly to the bathroom. I washed it off with lukewarm water as best I could. I remember thinking how many black guys have had this very mouthpiece in their mouths before. I also remember thinking why would it make a difference being in a black mouth as opposed to a white one. I quickly came to the conclusion it made no difference and there was no way I was not sparring today, so in my mouth it went.

Being the only white guy in the room hundreds of times over throughout the course of an eleven year professional career taught me many things. The most important being the ability to be totally at ease around black people. I had to develop a singular strength within myself to accomplish this. What I mean when I say singular is finding myself as the minority on a day in day out situation.

I attended a predominantly white high school and I lived in a totally white neighborhood until I left for college. I was never in the minority until that day I crossed the railroad tracks in Laurel, Mississippi. It’s easy to feel strong and at ease when you are walking around as the majority, but finding yourself as the minority requires the development of a singular type of strength in a person. In doing this it also gave me a glimpse of what a black man deals with everyday in almost every aspect of life here in America. I had to have a singular strength in a boxing gym, the black man must possess this singular strength almost everywhere he goes. Once I saw this and realized this truth, it changed my life culturally.

It’s very important for me to point out this cultural awakening was accidental, not intentional on my part; however, it would not have happened if I had not intentionally walked into that boxing gym. The byproduct of my desire to box was finding this truth. After you sweat, bleed, laugh, and cry with people it’s pretty damn hard to not see them when you look in the mirror.

Boxing has a way of exposing everything about a person unlike many other sports. Boxing, I would argue could be the most personal and intimate of all the sports in terms of competition. I can say that boxing was the catalyst in my racial awakening. The more I saw, the more I experienced alongside people of color helped shape the man I am today. I understand that very few white men will become boxers and experience my experiences; however, they can still intentionally move outside the white circles they live in and find their singular strength.

Recent Comments