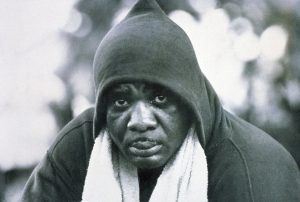

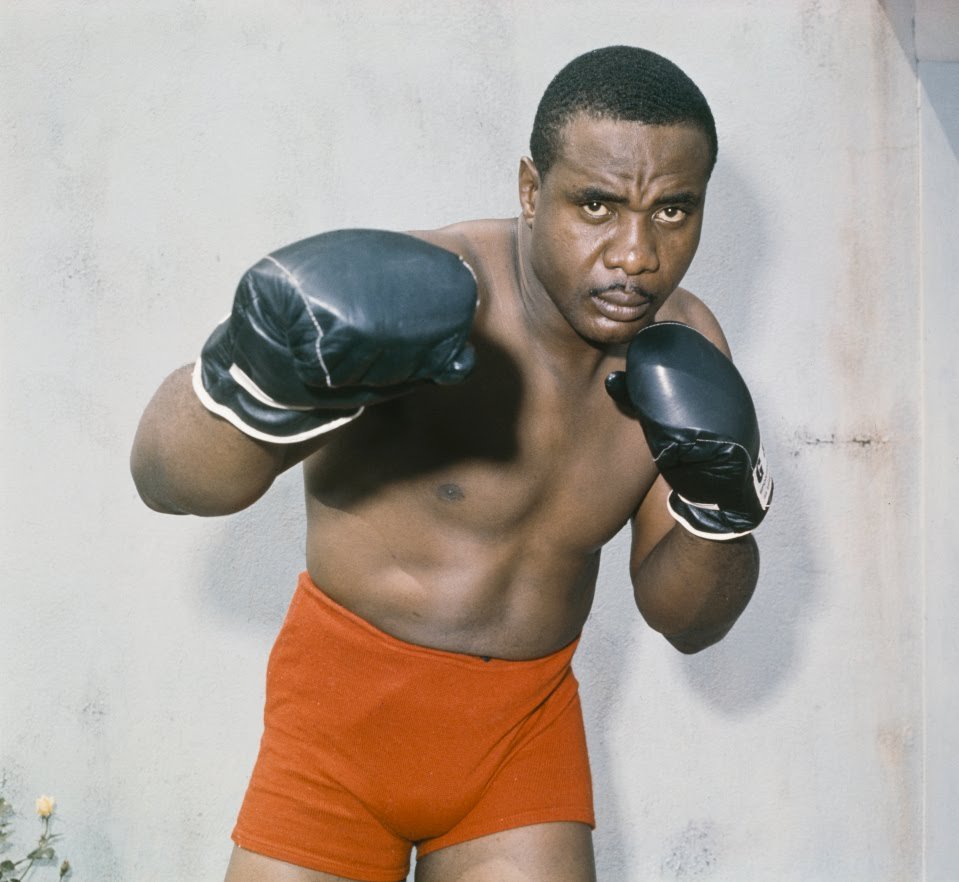

BOXING legend Sonny Liston was murdered by the MAFIA in a death staged to look like an overdose, a new documentary has claimed.

The former heavyweight champion is perhaps best known for being laid out on the canvas by Muhammad Ali in one of the sports most iconic bouts.

But less than six years after the controversial first round KO the legend was found dead by his wife Geraldine at their home in Las Vegas.

At the time it was thought he had overdosed on heroin, despite his well known fear of needles.

But now the true story behind his supposed OD, his enigmatic life, and connection to organised crime are examined in Showtime’s documentary, ‘Pariah: The Lives and Deaths of Sonny Liston,’ which premieres tonight.

In the programme, a former fight fixer claims Liston was supposed to take a dive in his last fight.

When he didn’t, he reportedly lost the Mafia a lot of money.

A coroner also suggested that the amount of heroin in his system wouldn’t have caused an overdose.

Directed by Simon George and based on Shaun Assael’s investigative book: “The Murder of Sonny Liston: Las Vegas, Heroin, and Heavyweights,” the film does more than simply rattle off a few conspiracy theories.

Coroner Mark Herman said the amount of heroin in his system was too small to have caused an overdose.

Whether he injected it or snorted it is another matter as despite the presence of needle marks, no syringe was ever found at the scene.

“Sonny was deathly afraid of needles, he and I had the same dentist… he wouldn’t even take Novocain.’” said Philadelphia Daily News sports writer Jack McKinney.

If Liston was murdered in a staged overdose, it’s possible that his killer was unaware of his needle phobia.

“I am willing to entertain the idea that it was an overdose, but not an accidental one,” Assael said. “The preponderance of evidence I found suggests that it is more than likely he was killed than not.”

“There was enough to recommend two or three different suspects. I was unable to land on one definitive [suspect].”

Liston was born in Forrest City, Arkansas, US, possibly in the early 1930s – the day and year are unknown. He was the 24th child of a “miserable miscreant” sharecropper father.

He wound up in St. Louis as a teen and began robbing restaurants and petrol stations, landing himself in prison which is where he learned to box.

When Liston became the top challenger to champion Floyd Patterson by 1960, it was a national scandal.

Congress debated whether Liston — whose criminal record included breaking a policeman’s leg in 1956 — was civilised enough to get into a boxing ring.

Testifying before a Senate committee, Liston said he had no education, was forced to work from a young age to help feed his father’s 25 children and could sign his name but not write his own address.

He also was asked about mob-connected promoters he dealt with and said, “I wouldn’t pass judgment on no one. I haven’t been perfect myself.”

The controversy became a flashpoint. Baseball’s Jackie Robinson said he wished Liston’s record were better but that he deserved the title shot, while President John F. Kennedy “urged Patterson to find [an opponent] with a better character”.

Liston got his title shot in 1962, winning the belt in the first heavyweight title fight to be decided in the first round.

Patterson got a rematch a year later but lost again by first-round knockout – this time even faster.

While training for the rematch in Las Vegas, according to Assael, Liston met a well-connected bookie named Ash Resnick, who made himself Liston’s personal concierge, “offering Sonny everything from fine clothes to consorts,” and became part of his inner circle.

One of Resnick’s best friends was boxing legend Joe Louis, who would later become close to Liston.

According to the FBI, Resnick used Louis as a “bodyguard companion” — an enforcer — on collection calls.

Cassius Clay – who later changed his name to Muhammad Ali – was Liston’s next challenger.

A gambling associate of Resnick’s later told the FBI that Resnick advised him a few days before the fight that Liston would win in the second round, but then called a few hours before the bout saying to forget the advice.

Liston lost the title to Clay, and the associate told the FBI, “Resnick knew that Liston was going to lose.”

Clay won a rematch in 1965 knockout. But the winning punch looked to many like it barely made contact and many were convinced it was a fix.

According to Assael, a theory emerged that Resnick made a deal with the Nation of Islam, which was connected to Ali, to have Liston take a dive in exchange for a percentage of Ali’s future earnings.

Nothing was ever proven, but Nevada state assemblyman Gene Collins told Assael that in 1970, as Ali prepared to fight Joe Frazier, Liston told him and others that “he had a portion of Ali’s contract”.

Another friend of Liston’s said something similar, claiming he said “he’d have money for the rest of his life.”

As for his own career, Liston went on to fight many has-beens but never returned to his former glory as a boxer.

By the late 1960s, according to Assael, Liston was using heroin and had become an enforcer for a drug dealer named Robert Chudnick, whose own celebrity made him as surprising a dealer as Liston was a collector.

The white, red-haired Chudnick was a famous jazz trumpet player known as Red Rodney.

He replaced Miles Davis in Charlie Parker’s band, sat in with Doc Severinsen’s band on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show when he was in LA and was regularly hired for sessions by the likes of Elvis Presley, Ella Fitzgerald and Barbra Streisand.

But Chudnick, a “compulsive thief,” never hit the career heights of a Davis or Parker, and distress over his life led him first to shoot heroin, then to sell it.

Chudnick enlisted his teenage son Mark to work with him, and Mark and Liston became a collections team.

In February 1969, Assael writes, Liston was at the home of a beautician and drug dealer named Earl Cage when it was raided by the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD) — the precursor to the DEA — and the Las Vegas police.

Everyone was arrested except for Liston, who was mysteriously released.

By 1970, dealer Chudnick started to believe Liston was untrustworthy and told his son Mark to stop dealing with him.

But while Chudnick was out of town for a gig, Liston came to his house looking for drugs.

Mark tried to turn him away but Liston barged in and searched the house, slamming the teen against the wall before leaving.

On January 5,1971, Liston’s wife, Geraldine, flew home from a New Year’s trip to find the boxer “lying bloody against the bed, blood covering an undershirt that barely covered his bloated body.”

He had been dead for several days, with drug paraphernalia laying next to him.

An initial autopsy found the cause of death inconclusive, noting only that it may have been related to heroin.

In 1982, a police informant named Irwin Peters walked into a Las Vegas police station with a remarkable story to tell.

He said Larry Gandy, a retired Vegas cop revered by everyone in the department, had become a burglar and was about to pull off a heist.

He also said Gandy had killed Liston, suggesting that Resnick had hired Gandy to subject Liston to an overdose after he and the boxer battled over money.

A police sting proved at least some of Peters’ information to be true — Gandy had become a thief and was caught in the act and arrested.

The officer Peters spoke to, Gary Beckwith, had been one of the officers called to the scene after Liston died. Thinking back, he remembered seeing Gandy there as well.

But with no evidence for murder and a strong case for burglary, the police went with the case they had. Gandy got 10 years but had his sentence suspended.

Content courtesy of The Sun, Photos courtesy of Getty Images.

Recent Comments