By Joseph Santoliquito,

The man—and voice—behind former two-division world champion Danny Garcia tells his story ahead of his son’s welterweight showdown versus Adrian Granados Saturday night on FOX.

That’s the way Angel Garcia had to communicate with his mother, fearful that those standing at the bus stop would hear their Spanish, a forbidden tongue back then in certain areas of Philadelphia in the late 1960s and 1970s. You spoke it and chances are a fight would break out moments later. Or they would be told, as Angel Garcia’s mother, Carmen Moulier, often was, to “shut the f— up!”

Angel was only six then. He didn’t understand what hate and bigotry is. This was way before his son, former two-division world champion Danny Garcia, was even a thought in his mind.

Halfway across the world, Vietnam was unfolding on TV screens across America. In Angel Garcia’s North Philly home, it was going on outside in the streets each night. Angel saw it first hand and there was no way—he used to vow to himself—that any of his children would have to endure the early life he had. Like getting up on chilly mornings at 3:00 a.m. to board a rickety bus to go pick blueberries in South Jersey. Angel did it from 10-years-old to 13, getting paid $1.10 a crate until 5:00 p.m.

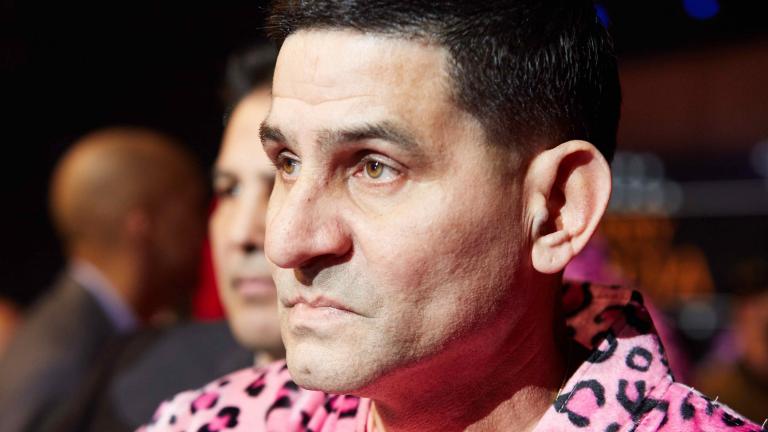

Angel Garcia is considered a volatile and polarizing fixture to those in boxing that don’t know him. At home, he’s a loving, caring father of four and a grandfather who’s far more intelligent than people give him credit for and often misunderstood by those who pay more attention to his antics than his message.

Angel’s son, Danny Garcia (34-2, 20 KOs), has a big fight this Saturday against Adrian Granados(20-6-2, 14 KOs) in the 12-round welterweight main event on PBC on Fox & Fox Deportes (8:00 p.m. ET/5:00 p.m. PT) at the Dignity Health Sports Park in Carson, California.

Danny, 31, is coming off a loss against Shawn Porter for the vacant WBC welterweight title last September. “Swift” has dropped two of his last three fights, though those defeats have come against the elite Porter and Keith Thurman. Still, it grates on Angel, as it always does, that Danny never gets the credit he deserves.

Carmen, who died in 1992 at 53 of liver cancer, would raise five children drawing $60 a week, working 12, 14, 16 hours a day, doing everything from picking blueberries to factory work. Danny, regrettably, faintly remembers his grandmother, who was a mix of Puerto Rican and French.

As you passed the invisible lines of demarcation, certain ethnicities would attack.

“My mom worked hard, she was a mother and a dad to me, she’s why who I am today,” Angel said in his trademark raspy voice. “My mom brought us to America when you couldn’t speak Spanish on the streets of Philly. My mother followed my uncles to America, after she broke up with my dad. I was six, growing up on Reese and Lehigh Streets in Philly.

“ We had it tough growing up. I dealt with real racism. ”Trainer – Angel Garcia

“We had it tough growing up. I dealt with real racism. It’s why it pisses me off today when people call me racist. I grew up in a time when I saw my mom get told to shut up at a bus stop because she was talking Spanish. She had to whisper Spanish to me, because we couldn’t speak it publicly. You had to watch your neighborhoods. You couldn’t be Puerto Rican in Philadelphia in the 1960s and ’70s.

“I’m a great father. I take care of my children. That came from my mother. It’s a shame my mom died so young. She got to see Danny born. She was young when she died. She took care of her children and took a lot of s—. I used to get called s— all the time. They used to say to me, ‘Get the f— out of this country you f—– s—.’ I got chased so many times I can’t even remember, and that was by all the gangs in the city.

“They would ask you for a quarter, and if you didn’t have one, they would smack the s— out of you. That’s where I came from and there is no way I was going to bring my children up in that kind of environment.”

So, Angel, who just turned 56 yet looks considerably younger, worked odd jobs, met different people, and like a sponge, learned and absorbed; reshaped, then learned and absorbed.

Sitting close by was Danny, who just nodded his head. He’s heard the storied a million times, and with his daughter Philly, Angel will no doubt impart his wisdom to her as she gets older.

There is one thing Danny stresses.

“He’s my dad, but I want to get something straight, I look like my mom,” says Danny, as they both looked at each other and burst into laughter.

“Hey, people think I’m crazy, and they can think what they want,” said Angel, who survived throat cancer when he was 39. “We live in a time today when you can’t even speak. You can’t even fart too loud. I grew up when police smacked you around—and you couldn’t say s— about it. Now, a cop can’t blink without getting in trouble.

“They need me as president. I would change all of this around. Donald Trump can run the money, while I run the country. We lost that hunger. People in America aren’t hungry anymore.”

As for Granados, Angel has no worries.

“It’s all about team work, it’s always been about team work,” Danny says. “Everyone has to have a great teacher or mentor on their way to the top. My father doesn’t get the credit he deserves; absolutely not. You have to sometimes let politics be politics. I know I wouldn’t be where I am today without my dad.”

As Danny was finishing his workout three weeks prior to facing Granados, Angel had one more thing to say to a passing visitor before he left.

But first, it came with a stealthy survey of the Swift gym. Angels’ eyes went right, then left, just to make sure Danny wasn’t within listening distance. Then Angel instinctively cupped his hand over his mouth and whispered to the guest in a cracked voice, “I’m very proud of Danny!”

Article courtesy of Joseph Santoliquito & PBC

Recent Comments